The infestation of local ash trees with the emerald ash borer has progressed to the degree that arborists and tree wardens across the area are pessimistic about its survival. “Foresters tell me that within ten years there won’t be any ash trees left,” said Woodbridge Operations Manager and Tree Warden Warren Connors. Four years after the invasive beetle was first discovered in this area, he is noticing more and more dead and diseased trees as he travels along the roads. For municipalities and landowners alike, that means applying more resources to watch out for the safety of people and buildings. “Every tree warden is having the same problem,” he said. For the most part, once the problem becomes evident, it is too late to save the tree, Connors said.

By the beginning of March he had exhausted the tree maintenance budget for this fiscal year. From here on out the removal of unsafe trees will have to be paid for from contingency or other budget lines items. The town budgeted $50,000 this Fiscal Year, but requested $60,000 for next year, in an effort to “keep up” with the rate of decay. In spite of a tough budget year, the town recognized the need for additional monies in that department.

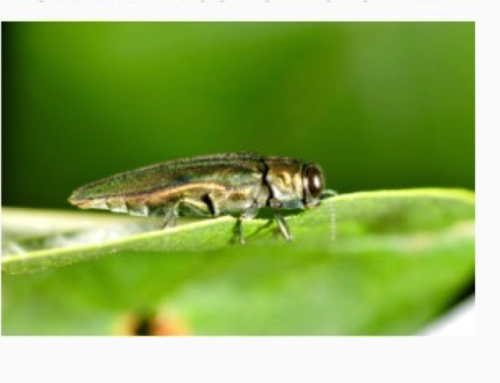

Emerald Ash Borer: The green beetle, which officials think arrived in the Detroit area from Asia in wood packaging some 15 years ago, spread like wildfire among the North American ash trees. It will lay its eggs under the bark of the tree, where the larvae feed off the tree’s nutrients and water. Eventually, the growing larvae will prevent these nutrients from reaching the crown, which causes disease. The wood becomes dry and pulp-like, Connors said. When a limb hits the road, it pulverizes, one tell-tale sign of disease. Typically the ash crown will be the first to show disease and break off, then the bark sheds in places (“blonding”), until the trunk eventually collapses on itself.

Another sign of infestation are the tell-tale holes produced by the fully developed beetle, as they emerge from the wood, where they produced serpentine tunnels under the bark. Woodpeckers are popular visitors, as they have easy access to the beetles through the softened bark.

Connors has developed an eye for diseased ash trees, even though the damage may not be visible to the untrained eye. He keeps a list of trees on town property that need to be addressed – several trees on Acorn Hill and Peck Hill, on Pease and North Pease roads, also a handful of trees at the Pease Road entrance to the High School. He relies on residents’ cooperation to point him to those trees that may constitute a risk. His charge is to manage the trees on town property, those along the roads – typically ten feet from the side of the road – and around public buildings. Connors assesses the risk of each tree to cause injury or damage to buildings before he decides to have the tree removed. He contracts the job out. In late April crews cut down some 14 trees on the side of the firehouse, as they were dead or diseased and causing a threat to the building as well as the firemen and walking trails.

Property owners face decisions: Property owners who have ash trees on their land will face similar questions. Should they treat the tree or take it down? Richard Lewis III, of Woodbridge Estate Care, offers his customers a regimen of pesticide injections, which can kill the beetle and help preserve the tree. However, at this point it’s almost too late. “You could have had a chance if you had started three years ago,” he said.

Cost of a treatment is based on the diameter of the trunk. An 18” tree will cost some $180 per treatment, and at this point has a 50-50 chance of success, he said. The treatment will need to be repeated annually to ensure the tree’s continued health. In most cases, it becomes an economic decision whether property owners choose the pesticide treatment or to have the tree removed. The decision also will depend on how close the tree is to the house or other buildings. More often than not, ash trees self-seeded and will show up in clusters. If a property owner has seven ash trees that all die at the same time, they all need to be addressed at the same time, Lewis said. Those are the considerations homeowners may face.

“It’s definitely a public safety problem,” he said. When people are walking along the road near diseased trees, “you should think twice which side of the road you walk on,” he said. The Blue Trails which run through the Alice Newton Street Park and other areas of town have many ash trees, most of which can be expected to be diseased, he said. He said he recommended to the Park Association leaders to have a forester harvest all the ash trees before they cause a problem.

In Bethany, the South Central Regional Water Authority had two timber sales in 2015, the first one of which in January was very successful, said the Water Authority forester, Nick Zito. But there is not much left in terms of ash trees, and the wood quality is so poor it can barely be used for fire wood.

Bethany is considered the “epicenter” of the emerald ash borer infestation in Connecticut. Eversource, the electric utility, took down some 900 trees there last year. Nationwide, millions of trees have died in the past 15 years since the emerald ash borer made its appearance in North America. Drought and other environmental stressors have made the trees more susceptible to the beetle infestation.

Luckily, the large variety of species in this area has helped keep the woods in Woodbridge. Ash trees only constitute about 4% of the tree population in Connecticut, even if they could be as high as 20% in some urban areas, according to the DEEP website on the subject. For further information: http://www.emeraldashborer.info/ or http://www.ct.gov/deep/cwp/view.asp?a=2697&q=464598&deepNav_GID=1631.